Eye on the Prize

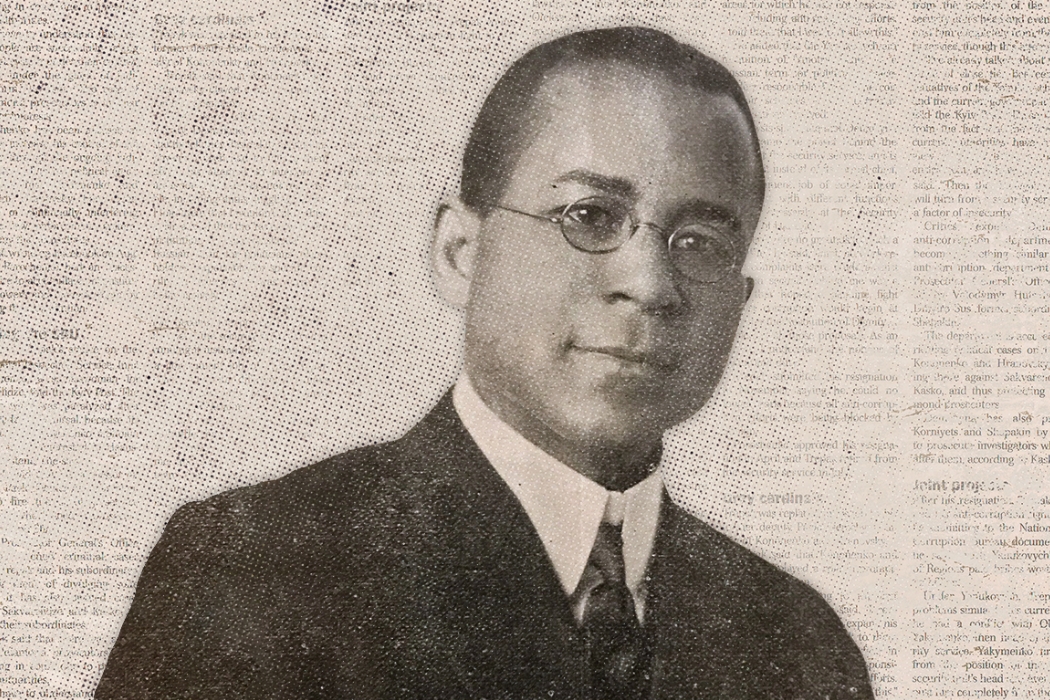

The 1895 Arbutus lists among the graduating seniors a math major named Marcellus Neal. With that announcement, history was made. Neal had officially become the first Black student to graduate from Indiana University.

Neal, BA 1895, was born in Lebanon, Tenn., in 1870, two years after the 17th President of the United States, Andrew Johnson, was impeached for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” The charges stemmed from a dispute between Johnson and Congress over how to rebuild the Union after the Civil War. The House impeached him, but the Senate tally was one vote shy of the two-thirds majority needed to remove Johnson from office.

It was in that atmosphere that Neal’s family moved out of Tennessee and settled in Greenfield, Ind.

Indiana had recently begun allowing Black students to enter the public school system, and Neal enrolled. He graduated from high school in the spring of 1891 with a strong academic record and a substantial scholarship to Indiana University. He took advantage of the offer and entered IU that fall.

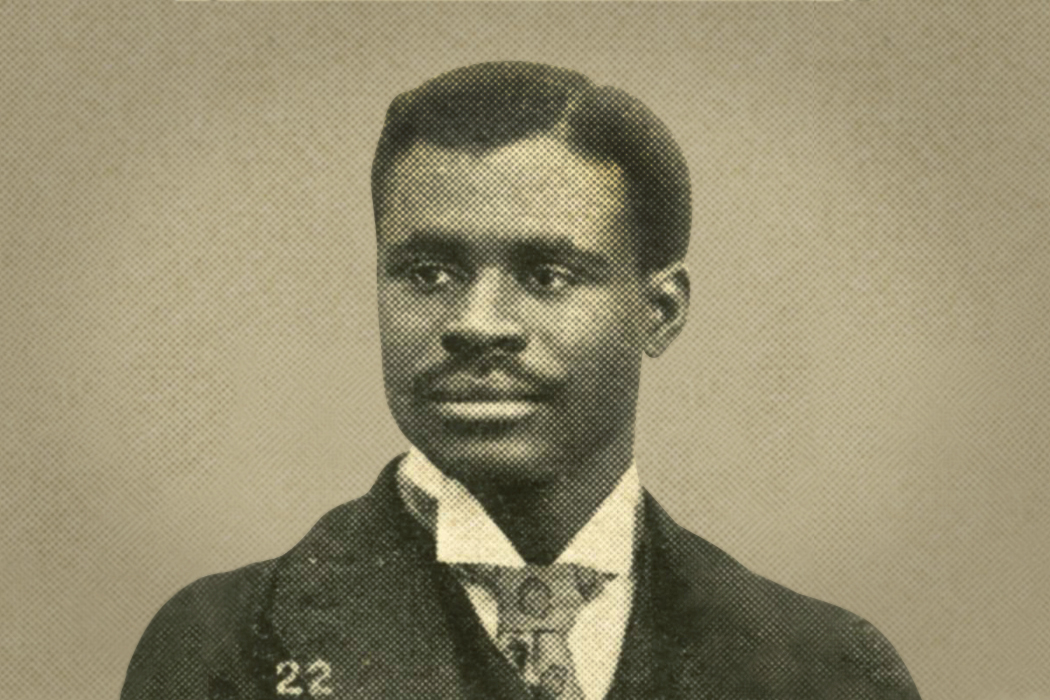

There were at least a few other Black students on campus during Neal’s time. The IU football team of 1893, for example, featured Preston Eagleson in the “left half” position.

Neal excelled at IU. The university at the time had a grading system that consisted of three levels, and Neal earned top echelon marks in most of his courses.

Facing Adversity

The 19th century was a difficult time for the Black community, and IU was not immune to racial tensions.

Given the racist and segregationist environment, and the economic and social hardships that Black students suffered as a result, it’s unsurprising that no Black student before Neal was able to persevere through the entire four-year program and earn a degree.

Neal himself just barely made it. In May of his senior year, he wrote the following letter:

“To the President and Committee on Student Affairs: Owing to the serious illness of my father and the condition of my financial affairs, it will be almost impossible for me to remain in the university until the close of the term. My work in the university is practically completed. I have conferred with each of the professors under whom I have worked and have obtained their consent.”

His studies to date were enough to satisfy the degree requirements, and in 1895 Indiana University awarded a diploma to a Black student for the first time in its history.

Financial troubles continued to plague Neal. In July of 1896, he wrote IU President Joseph Swain, MS 1885, that he had not yet found work and could not pay the money he still owed the university for various fees. He promised to pay the balance as soon as he was employed, and he said he hoped the president would find that arrangement satisfactory. The amount owed: $10.20.

He eventually found some temporary teaching positions, and he spent the next 10 years traveling and taking graduate courses. He then became the head of the science department at Washington High School in Dallas, a position he held for more than two decades.

Neal then took a civil service position in Chicago. While there, he wrote a treatise on science and several political editorials for newspapers. He also played an active role in the Black communities of Chicago.

His life was on a strong and positive course, but it ended abruptly. He died Nov. 6, 1939, of injuries suffered in a hit-and-run accident. He is buried in the Mount Glenwood Cemetery in Glenwood, Ill.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 1995 issue of the IU Alumni Magazine. It is now part of our Black History Month series, IU’s Black History Makers.

Tags from the story

Written By

Michael Robert Evans

Michael Robert Evans, MA’98, PhD’99, was a freelance writer for the IU Alumni Magazine and associate professor of journalism at IU Bloomington. He is now vice president for academic affairs at Southern New Hampshire University.