Undoing Time

On April 25, 2016, Darryl Pinkins was released from prison after serving nearly 25 years for crimes he didn’t commit. During the long journey to clearing his name, his faith would sustain him, science would set him free, and an IU legal team would play a pivotal role in proving his innocence.

Crime and Punishment

Around 1 a.m. on December 7, 1989, a woman driving home was rear-ended at a stoplight in Hammond, Indiana. When she got out to check the damage, she was pulled into another car by three men. She was robbed and raped by five men before being returned to her car and permitted to drive home.

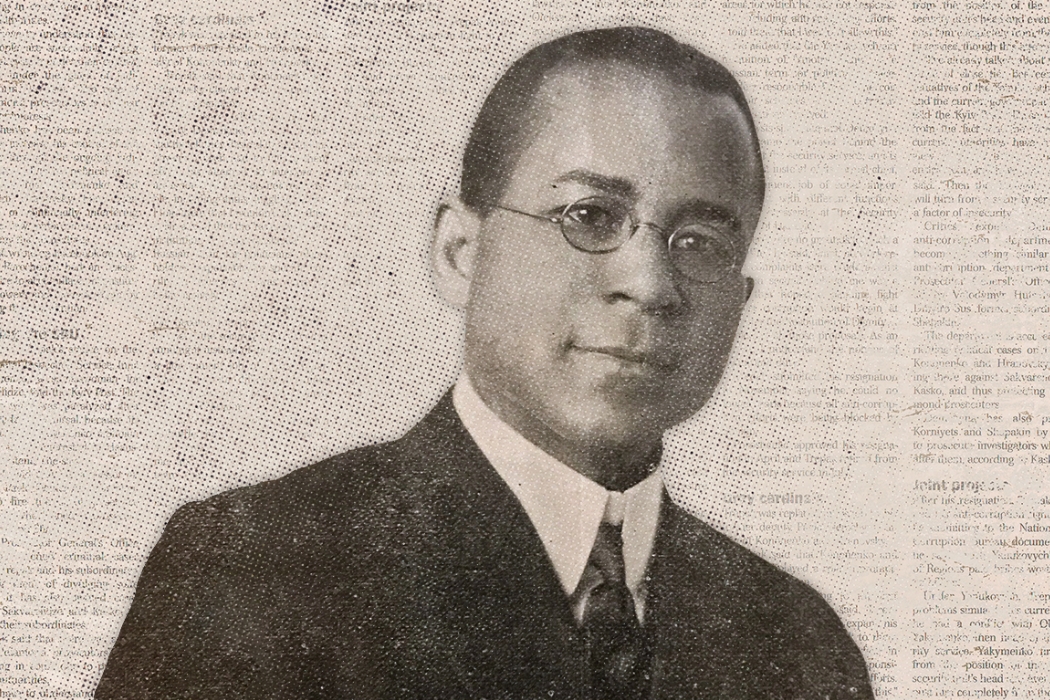

At the time, Pinkins was a 30-year-old father of three with one on the way. A Ball State graduate and Navy veteran, he was saving to buy his first house.

He worked at a Gary steel mill, where employees wore green coveralls—similar to coveralls used to cover the victim’s eyes during her assault. Never mind that Pinkins and two of his colleagues had reported their coveralls missing. Never mind their alibis. Never mind the lack of DNA evidence linking them to the crime.

The coveralls implicated Pinkins and two of his co-workers, and five months later the victim identified him as one of the perpetrators. Pinkins was convicted and sentenced to serve 65 years for robbery, rape, and criminal deviate conduct. He began his sentence at Michigan City Prison, a maximum security facility notorious for its violence and gang activity.

“Some of the particular personal things that I had to encounter—those are things that test your character,” Pinkins says. “No sense going into detail … just the mental anguish of prison is enough to put a man through change.”

Seeking Justice

Through the years, Pinkins maintained his innocence. His family stood by him, but they needed help—someone with legal expertise who believed in his innocence too.

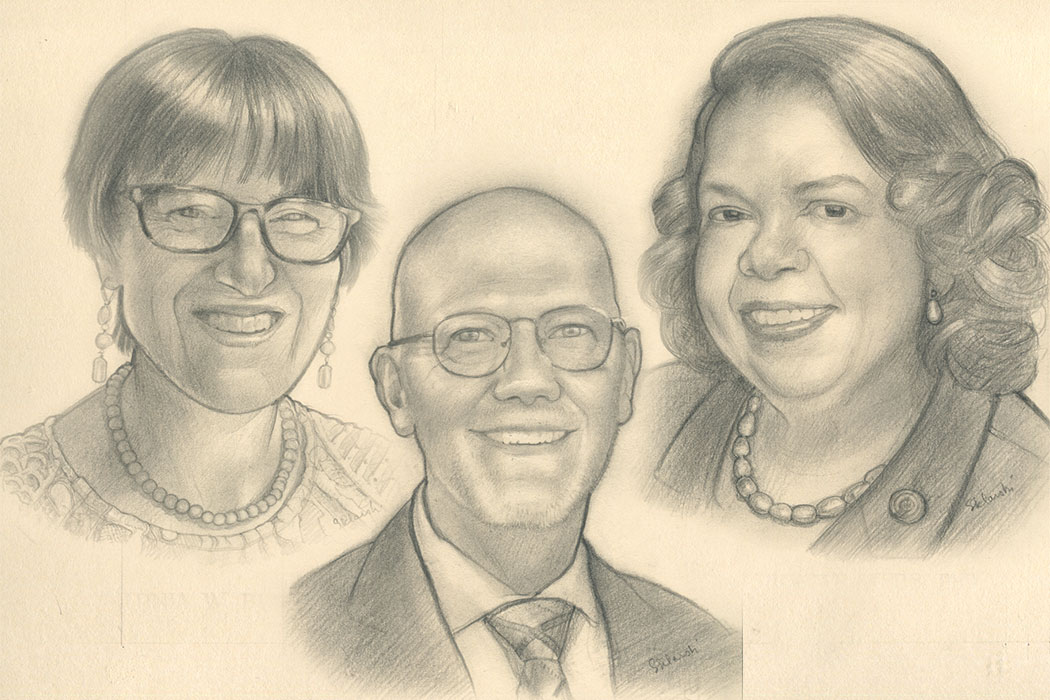

In 1999, Pinkins’ case came across the desk of Fran Watson, clinical professor of law in the IU McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis. Watson, a McKinney alumna, leads the school’s Wrongful Conviction Clinic, a member of the international Innocence Network.

When you can’t solve a situation yourself, you’ve got to have hope.

After reading through the details of the case, Watson was convinced that Pinkins was innocent, and she agreed to have the clinic take on his appeal.

“She became familiar with this case to the point where she was determined not to walk away from it,” Pinkins says.

Winning an exoneration is no easy feat, though—and working on cases in a clinic setting complicates things further. Watson divides her time between teaching and case work, manages multiple active cases at a time, and her student legal team changes every semester.

Despite these challenges, they forge ahead … because lives like Pinkins’ are on the line. For the better part of two decades and through six failed appeals, Watson and her clinic law students worked on Pinkins’ case.

“If you were to meet Mr. Pinkins and Mr. Glenn [one of Pinkins’ co-defendants], and you knew their families, you’d understand why you would never give up,” Watson says.

“Us fighting for them—even just visiting them, just introducing another few students to the tragedy of it all—it gave our clients hope, and it gave them self-respect, because they knew someone was out there who knew they were innocent.”

A Breakthrough

After nearly 17 years of exhausting what seemed like every option in Pinkins’ case, Watson became aware of a new technology in DNA processing that was ideal for identifying the men who actually committed the crimes for which Pinkins was serving time. A judge agreed to hear the new evidence.

Four days before the new hearing was set to take place, however, Watson got a call. Swayed by the new DNA findings, the prosecutor was filing a motion to throw out Pinkins’ conviction. The new evidence wouldn’t even need to be heard by a judge.

On the Friday before Pinkins was to be released, Watson arrived at the prison where he was currently being held. When Watson saw Pinkins that day, he was shuffling down the hall toward her, shackles restraining him at the wrists and ankles, and he was

smiling. He was wearing the orange jumpsuit that he’d wear over the weekend and then, come Monday, never again.

Away from the crowds and cameras that had gathered outside, with the restraints removed from his arms and legs, Pinkins and Watson had a few minutes to talk in a quiet corner of the warden’s office. They sat close, facing each other, knee to knee, and held each other’s hands. Watson looked him in the eyes and said the words they’d both been waiting to hear for too many years.

“It’s over.”

A Fresh Start

Today, Pinkins says he’s focused on supporting his family and keeping it strong. In prison, he was certified in Braille, which will allow him to do something he loves: helping others.

“He’s in a really good place right now,” Watson says of the man who’s become like a brother to her. “He’s moving on, he’s going to try to pick up his life and go with it, and I’m really proud of that.”

As Pinkins reflects on where he is now, he says it’s all thanks to the combination of his family’s and Watson’s unfailing belief in him, and his own belief in God.

“My days are like everybody else’s, good and bad,” he says. “I just had to, over the years, remember: When you can’t solve a situation yourself, you’ve got to have hope, that whoever created this whole existence has a purpose. This may have been a tragic thing, but … everything comes out beautiful in the end.”

The IU McKinney School of Law Wrongful Conviction Clinic not only fights for clients like Pinkins; it also gives law students the chance to work on real cases—a formative experience for some of the top lawyers in Indiana and beyond.

To support the critical work of the Wrongful Conviction Clinic—and the ethical, driven lawyers it helps shape—contact Lisa Schrage, director of development services at the Robert H. McKinney School of Law, at 317-274-1906 or lschrage@iu.edu.

This article was originally published in the fall 2016 issue of Imagine magazine.

Tags from the story

Written By

Andrea Alumbaugh

A native Hoosier, Andrea Alumbaugh is a graduate of IU (BAJ’08) and a senior writer at the IU Foundation.