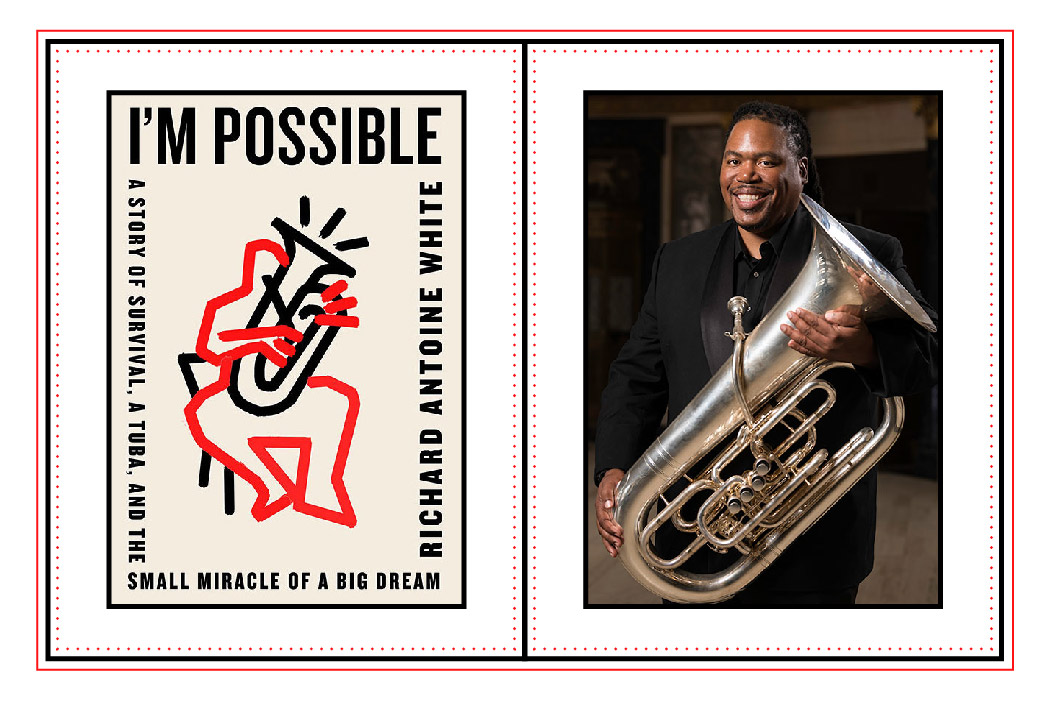

Excerpt: I’m Possible by Richard Antoine White

Young Richard Antoine White and his mother don’t have a key to a room or a house. Sometimes they have shelter, but they never have a place to call home. Still, they have each other, and Richard believes he can look after his mother, even as she struggles with alcoholism and sometimes disappears, sending Richard into loops of visiting familiar spots until he finds her again. And he always does—until one night, when he almost dies searching for her in the snow and is taken in by his adoptive grandparents.

Living with his grandparents is an adjustment with rules and routines, but when Richard joins band for something to do, he unexpectedly discovers a talent and a sense of purpose. Taking up the tuba feels like something he can do that belongs to him, and playing music is like a light going on in the dark. Soon Richard gains acceptance to the prestigious Baltimore School for the Arts, and he continues thriving in his musical studies at the Peabody Conservatory and beyond, even as he navigates racial and socioeconomic disparities as one of few Black students in his programs.

With fierce determination, Richard pushes forward on his remarkable path, eventually securing a coveted spot in a symphony orchestra and becoming the first African American to earn a doctorate in music for tuba performance. A professor, mentor, and motivational speaker, Richard now shares his extraordinary story—of dreaming big, impossible dreams and making them come true.

Chapter 9

Band Nerd

“What’s that?” I pointed at the sousaphone Corey was playing. “I want to play that.” Nothing else in the band room looked like it. Nothing else sounded like it.

When Dontae and I got to Fallstaff Middle School we were still playing trumpets, but I was trumpet eighteen out of twenty-eight. When Mr. Burns, the band director, opened the big metal door to the giant instrument vault, I saw that instrument—the big curve of its bell, its three valves wrapped in beautiful circuitry, and its singularity. It was the only one I wanted.

Mr. Burns smiled at my scrawny little self. I was pretty tall, but still whip thin. “Well, how about you move to baritone horn first?” So I played baritone for a little while, and then at the end of seventh grade I moved to the sousaphone. By then, I was the only sousaphone player, but that had some disadvantages.

Beside the green chalkboard was the Musical Star Chart—a grid with gold stars and colorful badges. For every pop song you mastered, you got a star. The wall was filled with stars earned by the flutists and trumpeters for being able to play the theme song to Sanford and Son or The Cosby Show.

I wanted to play Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called to Say I Love You” so badly. I asked Mr. Burns about the music for sousaphone.

“No one has ever requested this, so I don’t have an arrangement for sousaphone.”

“Oh, so I can’t play any stars?” I looked at him with the biggest, saddest puppy-dog eyes.

So Mr. Burns arranged all the popular tunes for the sousaphone. He would teach us by rote. He would play whatever I was learning on the piano and then I would try to play it back. He’d play, Dee Deee Di.

I’d play, Dee Dee Dooooo.

He’d say, “No.”

We’d do it again and again until I played Dee Deee Di, just right. When I wasn’t working with Mr. Burns, I would be in a tiny soundproof box of a practice room with a cassette tape.

I’d press Play and a voice would say, “This is B-flat. Doooo. Pause the tape. When you have mastered B-flat, go to C.”

Then I would play Do-Re, Do-Me, Do-Fa, Do-Sol, until I could hit each note again and again.

I was the first sousaphone player to get all the stars on the board. But I was not getting any stars in my academic classes. Nor was I getting good marks for behavior. I was always being called into the principal’s office. For fights. For grades. For attitude. That big brown bench facing the secretary’s desk practically had my butt imprinted on it; I sat on it more than I sat in class. Social studies with Ms. Jackson had way too many cute girls to impress.

One day Grandma arrived and we went in together.

Ms. Shaw, the vice principal, eyed me, and then she looked at Grandma. “Richard has …”

I broke in, “But I’m not …”

“Excuse me. I’m talking,” Ms. Shaw said sharply.

Then quick as can be, I flipped, “Excuse me, I’m talking.” Heart pounding.

Ms. Shaw’s jaw flapped open, but no sound came out.

Grandma roared, “EXCUUUUUUSE me. You must have lost your damn mind. I will come up to this school and whip your ass in front of the whole class if you don’t change your attitude.”

I stayed quiet. I knew she wasn’t bluffing. Anger was bubbling out of her, her voice was tight and loud, and then all of a sudden she was crying.

“Me and your grandpa are trying our best. We’re giving you all we can. We really need you to change.” She was fishing in her purse for a tissue.

Ms. Shaw held out a box of Kleenex.

“Lord, I don’t know what else to do.” Grandma was rocking back and forth. “Lord have mercy.”

We left the office and I studied the ground, occasionally glancing up at Grandma, but her brow was still knitted together and I knew this was a storm that wouldn’t pass.

My feet dragged. I was afraid to be too close to her. I’d been hurt plenty, but I don’t think I’d hurt anyone that way before. I was ashamed. These people had never given up on me, but now, maybe they’d send me back to Mama.

I slid into the front seat of the red Pinto and stayed quiet.

I was on fire. I burned with shame—not that I’d done poorly in school, but that I had pushed Grandma beyond tears, beyond exhaustion, to the point where she was at her wit’s end.

When Granddad got home from work that night Grandma unloaded: “I was gonna kill him. Richard, I was gonna kill him! I’ve never been so embarrassed in my life. What are we gonna do? Lord. Lord. Lord.”

The next day when I walked into the kitchen all Grandma said to me was, “Ricky, you can do when you want to do, you just don’t want to.” Then she handed me an epic list of chores and left for work.

I got up the next day and did the chores before she woke up. As I wiped down the mopboard, I thought, Okay. Now what are you gonna tell me to do?

When she came downstairs later that morning I said, “I’ve taken out the trash, wiped down the trash can, put the dishes in the drying rack, swept the floors, and wiped down the mopboard.”

There must have been hubris in my tone because she swiftly said, “Well, then why don’t you clean the dishes in the china cabinet and wipe down the shelves.”

Her list of housework was endless. To my chores, I added my homework.

The worst punishment was that I had to drop out of band until my grades improved. I was stuck in typing down the hall, tortured by the sound of music echoing off the classroom walls of the band room as I tried to hunt and peck beneath the hard plastic baskets we had to place over the keyboards and our hands to keep us from hunting and pecking. My wrists chafed against the rough edges. The only thing I got from typing was motivation to get out of typing, which is not to say that I learned how to type. I sucked at typing. I was so terrible that I was going to fail, so they let me back into band.

I learned music by ear. I couldn’t read sheet music but I could play “I Just Called to Say I Love You” and an aria from Mozart’s The Magic Flute. That’s how I got into TWIGS—To Work in Gaining Skills—the junior program that was a sort of training ground for kids who wanted to get to Baltimore School for the Arts. Dontae, our friends Sandra and Maria, and I all auditioned for the free after-school arts program when they came recruiting at Fallstaff. Sandra got in for dance, Maria for theater, and Dontae for trumpet. We thought we were the kids from Fame. The band kids were my tribe. But with the TWIGS program, I was out of my element. The kids in TWIGS had been playing instruments for a lot longer than I had, they had private lessons, they could read sheet music, they owned their instruments. There weren’t a whole lot of brown kids running around TWIGS. It was Dontae, Sandra, Maria, me, and a whole bunch of white kids from different parts of the city.

My instructor was Ed Goldstein. We would meet at the Baltimore School for the Arts in a practice room on the fifth floor. Ed gave me assignments. He told me I had to get this book, Getchell’s First Book of Practical Studies for Tuba. Granddad and I didn’t even know where to get the book, so we drove all the way to Silver Spring, Maryland, to find it. Up to that point, I’d never practiced outside school. I didn’t know you were supposed to sit down and spend hours trying to learn the music. I didn’t have a recording of the music we were playing. I didn’t know how it was supposed to sound. I didn’t know I was supposed to be able to read music. I looked at those rows of black dots and saw ribbons of gibberish.

I could sense Ed’s frustration. I’d play and he’d say, “No. Do it again.” Round and round we went. I knew I wasn’t getting it, but I didn’t understand why or how to fix it. Everyone else understood it and I didn’t. How do you look at these obscure dots on the page and know what they mean? I wanted to be able to do that. Everything was new to me, but I was determined to grow great. I did not understand the meaning of the word “quit.” Once I got serious about sousaphone, Mr. Burns, the band director, would put the big white instrument in the back of his gold 1986 Honda Accord and take me home so I could practice over the weekend. Then, he’d pick me up Monday morning to bring me back to school. The instrument didn’t have a hard case, so we had to take it apart. We put the bell in first, and then the body of the sousaphone would have to be placed over the bell, so it would all fit in the trunk.

At school I had this crazy sousaphone chair—part seat, part instrument-holding contraption with three spidery prongs to support the body of my instrument. I was still a pretty scrawny kid and couldn’t hold the sousaphone and play it unsupported. But at home I didn’t have a sousaphone chair so I practiced a little bit at a time until my shoulder couldn’t take any more. I’d try to balance it on the chair in Grandpa Archie’s old room, then I’d crawl up under the sousaphone, shimmy up into its tubes, and play. That’s where Grandma found me practicing. I wanted to finish before Mama showed up for dinner.

The last time she had called, she had promised to bring me something.

“What is it?” I’d asked.

“Something,” she said, her voice full of mystery.

“What is it, Ma? What are you gonna bring me? Is it cars? Is it a truck?”

“I promise, I’m gonna bring you something.”

My imagination took off running. Maybe she’s going to bring a race car, or a spaceship. My mind went crazy. I asked Grandma what she thought it was. She just shrugged.

“Your mom is on the phone, Baby Ricky.” Her tone was clipped and I knew before I’d picked up the receiver that Mama wasn’t coming.

She explained that she didn’t have the bus fare. All I could do was mumble that I understood.

As I slipped back into my room, I could hear Grandma say, “You just don’t see him. You can’t keep doing this to the boy.”

I was torn. I loved my mom but I was old enough to understand that Grandma was right. I needed someone to take care of me.

I raised the sousaphone up and let my fingers fly over the valves. I played Do Do Doooooo Do Do Doooooo until my lips were numb and my fingers started to cramp.

By the end of seventh grade, I was the kid who played sousaphone. Or tuba, as all the non-band kids called it. Or the bugle, as my Granddad and the people in my neighborhood called it. Sousaphone. Tuba. Bugle. Whatever. I loved it.

It felt like something I could do that belonged to me. Something I could do that very few people could. Of course, it helped that I picked an instrument that no one else had wanted to play. It was a way for me to communicate with something that I understood on a really comforting level. It didn’t have to be explained in any complicated manner and I could do it as many times as it took to get it right. Playing music was like a light going on in the dark. Like seeing a star for the first time.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, check out our Q&A with Richard Antoine White or purchase his book.

Excerpt from I’m Possible by Richard Antoine White. Copyright © 2021 by Richard Antoine White. Reprinted by permission of Flatiron Books. All Rights Reserved.

Tags from the story

Written By

IUAA Staff