Reds Among the Cream and Crimson

When angry letters from Indiana citizens arrived in August 1946, IU President Herman B Wells, BS’24, MA’27, LLD’62, knew he had a problem on his hands.

“Take steps to fire the Reds connected with your school system. If they can’t find another position, Joe Stalin will welcome them with open arms. Gavit, Harper, and Mann, must go,” one letter said.

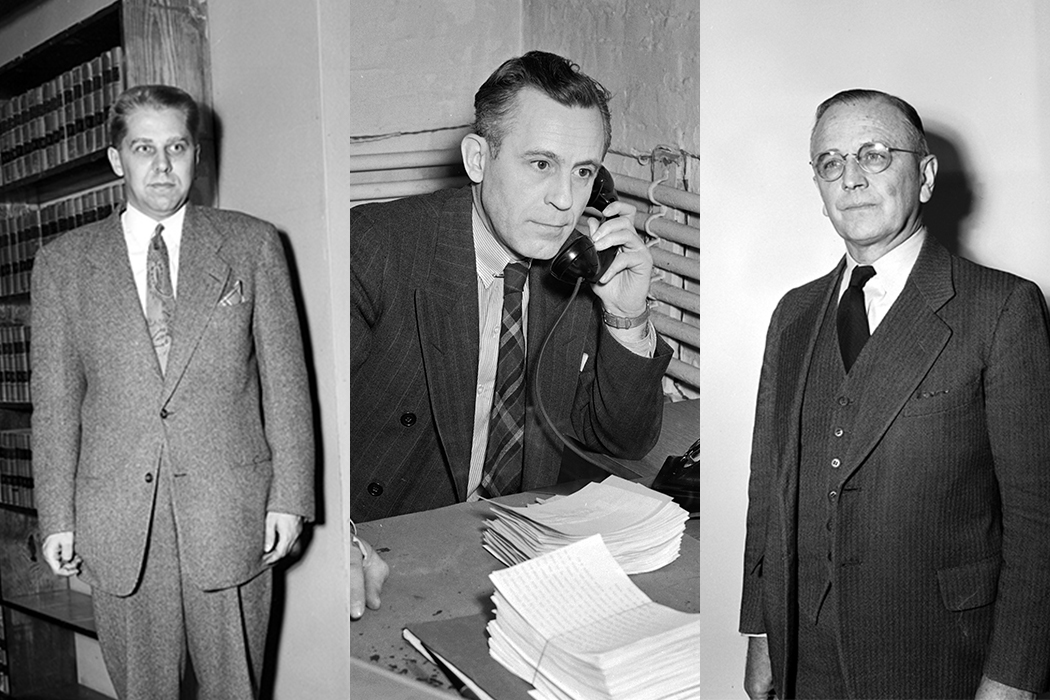

Three law school faculty members—Dean Bernard Gavit, Professor Fowler Harper, and Associate Professor Howard Mann—signed a July 29, 1946 letter directing Indiana Gov. Ralph Gates and the state Board of Election Commissioners to include the Communist Party on the state ballot. In doing so, they clearly didn’t anticipate the drama that would unfold over the next six months in Bloomington.

The signed letter from the trio of academics stated: “We support wholeheartedly the right of every minority party which can fulfill the statutory requirements to have its place on the ballot … none of the undersigned are either members or sympathizers with the Communist Party … this is a manner affecting deeply the civil liberties of all citizens which constitute the very cornerstone of our democratic system.”

In addition to the three IU professors, eight other signatories had agreed that the Communist Party should be represented on the ballot. The fact that the governor and the election commissioners concurred, and that the Communist Party candidates appeared on the ballot (and received about 900 votes for their top candidate), have become minor footnotes in history.

Despite Gov. Gates agreeing that the Communist Party had the right to appear on the ballot, he did not believe that three law professors from the state university had the right to advocate for it.

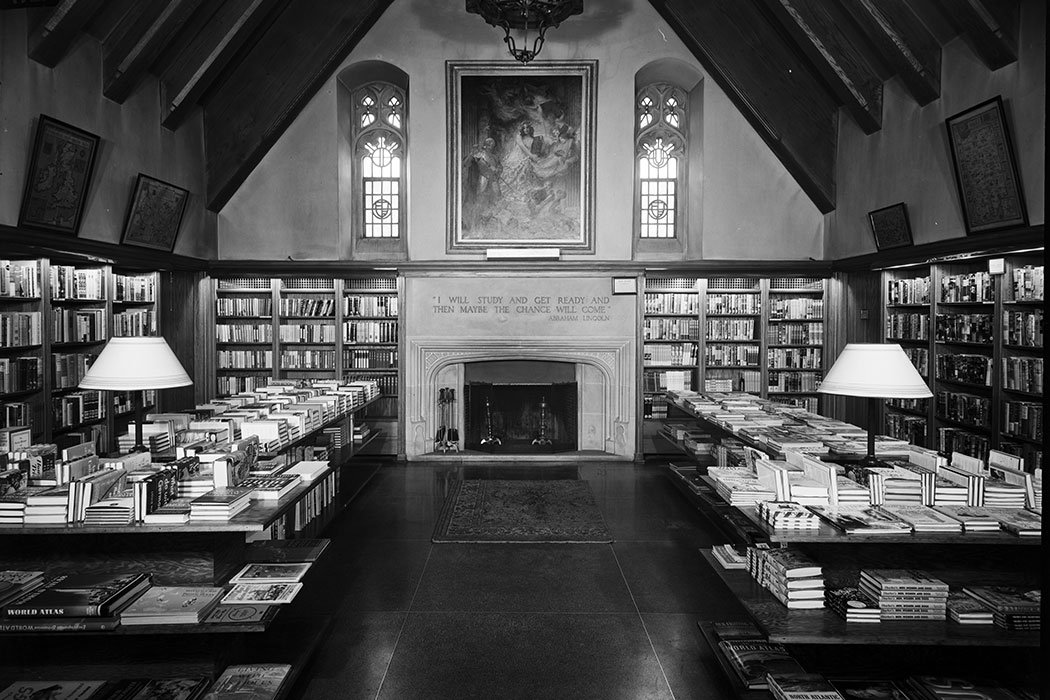

Meanwhile, Wells simply filed away the angry letters into his folder “Complaints and Criticisms, Letters of,” but would soon need more than 25 folders to house his “Communism,” “Communist Investigation,” and “Subversive Teaching Report” records.

Developed throughout the fall of 1946, the records were compiled at the prompting of Gov. Gates, who asked Board of Trustees President Ora Wildermuth, LLD’52, under pressure from The American Legion, that the university leadership review these professors.

This was a tricky situation for the board—half of the membership of the board were Legion members and most were appointed to their board positions by the governor. And it was a tricky situation for Wells as it tested the recently approved 1943 IU Policy on Academic Freedom and Tenure.

But for Wildermuth, who served from 1941–1945 on an Alien Enemy Hearing Board, ferreting out communists was not a new exercise. As the fall semester got underway, Wells attempted to satisfy the board’s concern by focusing a meeting of his administrative council on the matter, emphasizing “how important and serious, and really significant this thing was; that it took care and wisdom and authority to meet it.” But that was not sufficient.

On Sept. 16, 1946, Professor Harper tendered his resignation from IU but that was not sufficient for the board either.

So on December 3, Judge Wildermuth and President Wells dropped the gavel at 11:20 a.m. in Bryan Hall Room 200 (the trustee room adjacent to the president’s office) on an “investigation” that lasted more than 30 hours.

Twenty nine witnesses testified and 400 pages of documentation were recorded. The board sought to answer three questions:

1. Were IU faculty members using their positions to promote any communistic, un-American, unpatriotic, or subversive philosophy?

2. Have such philosophies existed among faculty or students?

3. Are the three law professors at fault for petitioning to include the Communist Party on the state ballot?

The Board started with testimony from representatives of The American Legion.

State Commander W. I. Brunton offered: “The American Legion does not subscribe to a theory that the ugly head of communism can be crushed in this country by ignoring its presence like an ostrich hides its head in the sand. Neither does The American Legion subscribe to a theory that communists should be placed on the ballot in order that we may know their strength. We of The American Legion are not interested in taking a census of rattlesnakes.”

Brunton acknowledged that the professors’ university affiliations may have been added to the offending letter after the professors signed it, referencing a clause at the bottom of the letter: “The above persons have signed this as individuals and their organizational connections are given only for identification.” Regardless, he said, “We are deeply concerned with this institution.”

William Sayer, The American Legion’s state adjutant, suggested the professors wanted to be agitators since the Communist Party “attempts to cause trouble between the negro race and the white race …”

After The Legion representatives spoke, each school dean affirmed to the board that no faculty members held communist leanings nor practiced communistic teachings. When that was not completely satisfactory, Wells asked each dean to return to his department, poll the faculty, and report back before the hearing ended the following day. Most of the students who appeared asked for clarification on the definition of communism before denying knowing any communist faculty members or students. A handful of witnesses shared the names of possible communist faculty members—at least two of whom had left IU in the previous year—and other witnesses connected communistic philosophies with socialized medicine and NAACP-related issues.

On the core issue, they heard directly from professors Gavit, Harper, and Mann. Professor Harper’s testimony concluded: “I wish only to affirm that I am not a political sympathizer with the Communist Party nor have I ever been in sympathy with its political philosophy, practices, or objectives. I have never attended a communist meeting in my life … I believe with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes that ‘the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas,’ and I support the right of all Americans to use the ballot to express their political convictions.”

Harper asked the board if he was free to share this statement with the press, to which Wildermuth (ironically) retorted, “You believe in free speech, I hope.”

In his testimony, Dean Gavit, a member of the IU law faculty since 1929 and dean since 1933, blamed Harper for being the instigator and admitted his poor judgment in signing the petition. He believed there would be a large number of signatories, not only the 11 whose names ended up on the letter. Interestingly, none of the other eight signatories were investigated for subversive activities, including the state senator and state representative who signed it.

Finally, Professor Mann, a member of the law school faculty for only two months, offered no opposition to the charge of poor judgment but did defend himself by saying that the institutional affiliations were not attached to the letter before he signed it, and that he would never embarrass the school by implying that his views officially represented the university’s.

Board members and Wells queried each of the three professors, and many other witnesses, on whether they had reviewed the relevant election code. When Dean of HPER and The Legion member, Willard Patty, responded that minority party representation was the reason for agreeing with the petition, the Trustees got defensive.

Trustee Allen: “… if we take that point of view I am convinced that the University is in an open fight.”

Dean Patty: “For what?”

Allen: “With the American Legion because they take—”

Patty: “You mean there is a group of people [who] insist the state university subscribe to the dogma that they happen to believe, is that it? In other words, it is not a free institution any longer, where we seek for truth?”

This was the core test of the board’s new 1943 Academic Freedom policy, which stated: “The University recognizes that the teacher, in speaking and writing outside of the institution upon subjects beyond the scope of his own field of study, is entitled to precisely the same freedom, but is subject to the same responsibility, as attaches to all other citizens.”

Formally, the Board and Wells reported to Gov. Gates in their December 15 letter that they found no evidence of communism among students or faculty. In response to the specific charges against Gavit, Harper, and Mann, they reported: “These three, each a veteran of one of our world wars, appeared at his own request, testified that they were not members of the Communist Party, and detested its philosophy. Each earnestly asserted his profound admiration for the Constitution and the American way of life.”

Informally, Trustee Feltus concluded that this whole episode was just a “tempest in a teapot.”

On Dec. 23, 1946, Wells sent a copy of the Trustees’ report to the campus faculty. And on Jan. 17, 1947, Fenwick T. Reed, assistant to President Wells, wrote to Frank A. White of The American Legion: “I think, unofficially, we are ready to get out of the commie investigation business, and will be glad to quit if you will.”

In the aftermath of the investigation, Gavit, Harper, and Mann filed a $600,000 libel suit against the Illinois Publishing Company, the Chicago Herald-American, the Hearst Corporation, and the Milwaukee Sentinel. The suits were settled out of court and retractions were published. Gavit, Harper, and Mann were not communists, but like many other faculty members around the country and at least 30 more at IU, they were forced to defend their loyalties to the cream and crimson, and not the Reds.

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine, a special six-issue magazine that highlights Bicentennial activities and shares untold stories from the dynamic history of Indiana University. Visit 200.iu.edu for more Bicentennial information.

Tags from the story

Written By

Kelly Kish

Kelly Kish, MA’02, PhD’10, is the director of IU’s Office of the Bicentennial and a contributor to 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine.