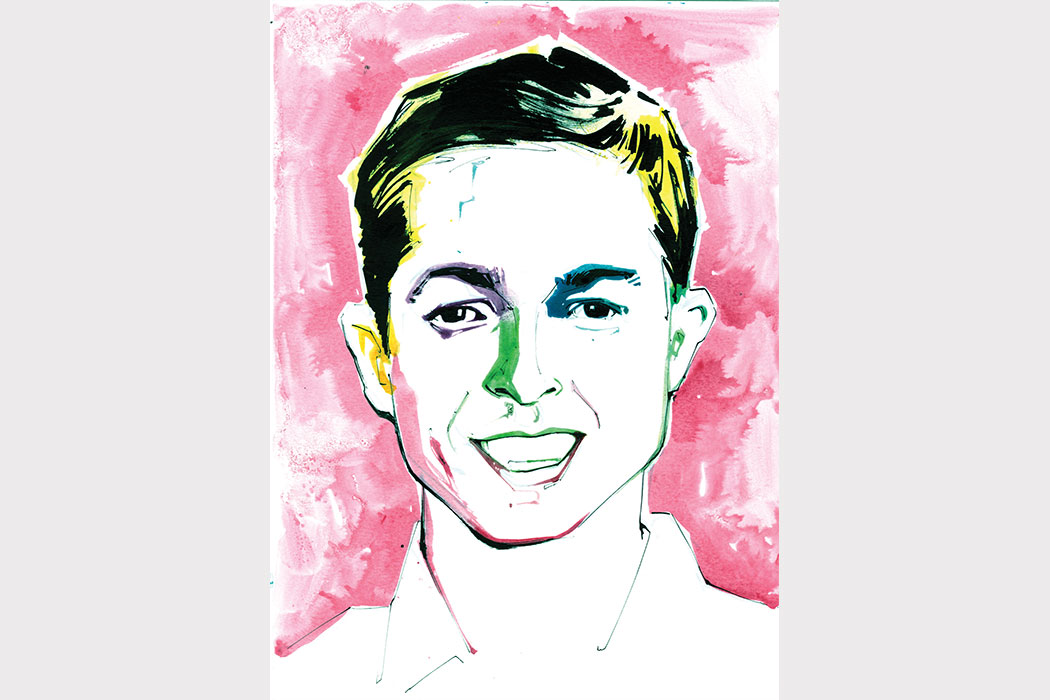

James Hamblin on ‘Maintaining a Human Body’

In his book, If Our Bodies Could Talk: A Guide to Operating and Maintaining a Human Body, James Hamblin, MD’09, tackles an array of questions—the ones we might be too hesitant to ask a doctor. Questions like: “How much sleep do I really need?”; “What’s up with multivitamins?”; and “Can I really ‘boost’ my immune system?.”

The book, which was featured in the Summer 2018 issue of the IU Alumni Magazine, developed from Hamblin’s online video series that is produced by The Atlantic, where he is a senior editor. He intends both the series and the book to be light and funny, and he uses interviews with scientists and doctors, as well as his own experiences to offer health advice.

Below are three questions and answers from his book. You can find more of Hamblin’s offbeat health perspectives on his video series webpage at TheAtlantic.com.

How can I tell if I’m beautiful? I mean in the purely superficial physical way that I know I shouldn’t care about but do because I am a person who exists in the world.

In 1909, Maksymilian Faktorowicz opened a beautification establishment in Los Angeles. Under the name Max Factor, he would become famous for his cosmetic products, which he sold as part of a pseudoscientific process of “diagnosing” abnormalities in people’s (mostly women’s) faces. He did this using a device he invented called the “beauty micrometer.” An elaborate hood of metallic bands held in place by an array of adjustable screws, the micrometer could be placed over a woman’s head and, as one of his ads at the time claimed, flaws almost invisible to the ordinary eye would become obvious. Then he could apply one of his “makeup” products, a term coined by Factor, to correct the flaw in this person: “If, for instance, the subject’s nose is slightly crooked—so slightly, in fact, that it escapes ordinary observation—the flaw is promptly detected by the instrument, and corrective makeup is applied by an experienced operator.” Even if putting on a metal hood that could tell people exactly why they’re not beautiful didn’t seem wrong on infinite levels, there was also the problem that Factor’s micrometer was contingent on an empirical definition of beauty. A device that tells people what’s wrong with them is predicated on an understanding of what is right. Max Factor’s approach is a textbook example of the sales tactic that is still so successful in selling body-improving products: convince people that there is a deficit in some concrete way, and then sell the antidote.

In the case of facial symmetry, some evolutionary biologists do believe that we are attracted to symmetric faces because they might indicate health and thus reproductive viability. From a strict perspective of evolutionary biology, someone with a prominent growth spiraling out of the side of their eye, for instance, might be viewed as a “maladaptive” choice for a mate. Instincts warn that this person may not survive through the gestation and child-rearing process, possibly not even conception. Best to move on.

But today most people survive long enough to reproduce and care not just for children, but grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and even domesticated cats. We can be less calculating about who to mate with. We can and do afford ourselves attraction not to some standard of normalcy, but to novelty and anomaly.

While Factor was convincing everyone that they were empirically inadequate based on a standard of normalcy that he created to sell products, the University of Michigan sociologist Charles Horton Cooley proposed a more nuanced approach, called “the looking glass self.” The idea was that we understand ourselves based not on some empirical idea of what is right or wrong about us, but from how others react to us. It’s difficult to believe you’re physically attractive when the world treats you otherwise, and vice versa. “The thing that moves us to pride or shame,” he wrote in 1922, “is not the mere mechanical reflection of ourselves, but an imputed sentiment, the imagined effect of this reflection upon another’s mind.”

Cooley repopularized the timeless idea that other people are not just part of our world, or even merely important to our understanding of ourselves: They are everything. Technically there are individual humans, just as technically coral is a collection of trillions of tiny sessile polyps, each as wide as the head of a pin. Alone in the sea, the polyps would be nothing. Together they are barrier reefs that sink ships.

The idea of a looking-glass self could seem disempowering, in that our understandings of ourselves are subject to the perceptions of others. A less devastating way of thinking about a world of looking-glass people, I think, is the idea that everywhere we go, not only are we surrounded by mirrors, but we are mirrors ourselves. It’s not the face in the Max Factor machine that matters, but the way that face is received. We can’t always choose our mirrors, but we can choose the kind of mirrors we will be—a kind mirror, or a malevolent mirror, or anything in between.

Why do I have dimples?

The muscle that pulls the corners of your mouth up and back (a “smile”) is called the zygomaticus. In people with dimples, that muscle is shorter than in the average person and may be forked into two ends, one of which is tethered to the dermis of the cheek, which then gets sucked inward when the person smiles. This is one way that beauty happens.

It’s an anatomical anomaly, sometimes even referred to as a “defect.” That understanding comes from an oft-cited theme in biology: that form necessarily correlates with function. Everything must happen for some reason, right? If dimples are a form without a clear function, then it’s easy to dismiss them as defects. It would be easier to write this book if it were the case that our body parts either had a clear purpose or else represented defects or diseases. But we’re more complex and interesting than that.

Biological function is a concept foundational to understanding health and disease, and it’s defined most often as the reason that a structure or process came to exist in a system. We have opposable thumbs, by the etiological theory of biological function, because they gave us an advantage in using certain tools.

While form can help inform our understanding of function, though, few cases are so clear-cut as thumbs. Some beards grow, some skin peels, and some cheeks dimple because they evolved to do so in certain people under certain conditions. There is no “purpose,” teleologically, for beards to grow or skin to peel or cheeks to dimple.

Theoretically all functions should together contribute to our fitness—to keeping us alive and well, as populations—but they may not do so individually. In isolation, a particular bodily function—like sleeping, for instance—may seem to be only a weakness. Sleeping is a time when we might be eaten by birds. But it exists, according to leading theorists on the still outstanding question of why we sleep, because it augments the functions of other body parts.

Elements of our forms may also be vestigial, like wisdom teeth or appendices, relics that lost function over time as systems changed. There is a spectrum of vestigiality, with some parts trending toward obsolescence but not yet useless. Other parts may never have been functional, but simply emerged as side effects of the functions of other parts. (These are sometimes known as “spandrels,” an allusion to decorative flourishes in architecture that serve no purpose in supporting the structure.)

The overarching idea is that almost no body part can be explained in isolation. They make sense only in the context of whole people, just like whole people make sense only in the context of whole populations. In a parallel world, dimples are anomalies we would attempt to prevent or correct. But in this time and place we choose to desire and envy them. Sometimes even to create them by force.

If I didn’t have dimples, could I give them to myself?

In 1936, entrepreneur Isabella Gilbert of Rochester, New York, advertised a “dimple machine” that consisted of a “face-fitting spring carrying two tiny knobs which press into the cheeks.” Over time, this force should produce “a fine set of dimples.”

It didn’t, though, because that is not how dimples work.

If only as an alternative to that particular form of hell, we may be fortunate that today a surgeon can perform a twenty-minute procedure to suture a cheek muscle known as the buccinator to the interior surface of the skin of a person’s skin, creating a dimple. It can all be done without ever puncturing the skin from the outside, coming through the inside of the cheek and cutting out a little bit of the cheek muscle, then running a suture through that muscle to the undersurface of the skin in the cheek. Pull it tight, and the skin will pucker. This is all done while the person is awake.

The puckering is exactly the sort of outcome that cosmetic surgeons spend years perfecting the art of suturing in order to avoid. So it took a truly heterodox thinker to invent the procedure. Based in Beverly Hills, plastic surgeon Gal Aharonov considers himself the father of the American trend in dimple surgeries. “It wasn’t a trend before I started doing it,” he told me. That’s a phrase I rarely trust, but he does appear to have created the dimpling technique, about ten years ago.

Excerpted from If Our Bodies Could Talk by James Hamblin. Copyright © 2016 by James Hamblin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

James Hamblin was featured in the Summer 2018 issue of the Indiana University Alumni Magazine, a magazine for members of the IU Alumni Association. View current and past issues of the IUAM.

Tags from the story

Written By

Lacy Nowling Whitaker

Lacy, a Bloomington native, earned two degrees from IU Bloomington (BA'08, MA'14) and is the Director of Content with the IU Alumni Association.